Tule Lake Research Project

The Foundation is assisting Roger Daniels, the nationally-known historian, and Barbara Takei, the writer and organizer on Tule Lake, in their archival research for a book they will jointly author. The book, on the subject of the Tule Lake concentration camp, will be published by the University of Washington Press and is tentatively titled "America's Worst Concentration Camp." The Foundation's funding comes from a federal grant. More on the Grant.

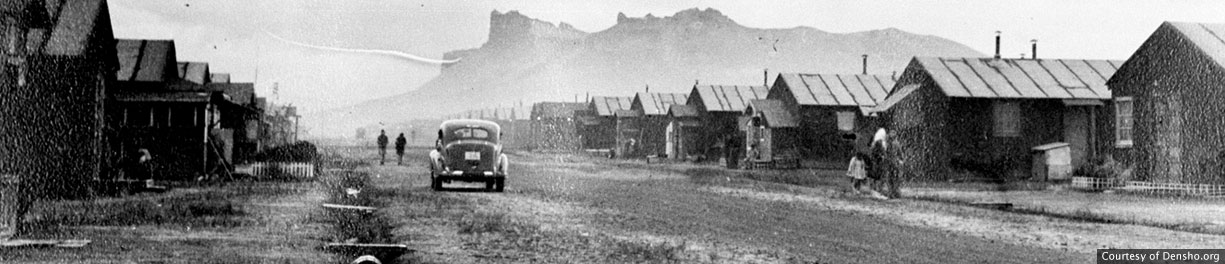

"No-Nos" Sent to Tule Lake

The Tule Lake Segregation Center, pictured above, was a notorious maximum-security concentration camp. Tule Lake was unique among the ten War Relocation Authority concentration camps because it was designated as the Segregation Center for Japanese Americans who refused to give "Yes-Yes" answers to the government's so-called "loyalty" questions.

The "Loyalty" Questions

Those questions read:

"27. Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?

"28. Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and foreswear any form of allegiance to the Japanese emperor, to any other foreign government, power or organization?"

"Loyalty" Questions: One Size Fits All

The government required answers to both of those questions in 1943 by every Japanese American over seventeen years old. It required answers about willingness to serve in the armed forces from those who because of age or gender would not be allowed to volunteer for combat. It required answers concerning foreswearing allegiance to Japan from U.S. citizens with no allegiance to Japan. It required answers concerning loyalty to the USA from the Issei or immigrant generation, who by discriminatory legislation were "aliens ineligible for citizenship" and thus were being asked to declare themselves stateless.

"Yes" Could Equal "No" and Punishment

The government treated Japanese Americans who refused to answer those senseless questions, who answered "no," or who qualified a "yes" answer in any way (for example, willing to serve if their families were released from incarceration), as answering "no." The so-called "no-nos," numbering over 12,000, were labeled "disloyals" and were punished by being segregated to Tule Lake, which became a maximum-security concentration camp and existed for months under martial law.

Protest of Injustice

The punishment and labeling ignored the fact that many no-nos were protesting the government's absurd questions and its unjust deprivation of civil liberties based solely on race. Instead, the government labeled protest as "disloyalty."

Renunciation and Planned Deportation

In 1944 the Department of Justice lobbied for, Congress passed, and the President signed, a statute allowing Japanese Americans to renounce their U.S. citizenship during wartime. Under this law, some 7,000 U.S. citizens at Tule Lake were stampeded into giving up their citizenship. The majority of renunciations took place during one month: December 1943. As a result, as planned by the government, the renunciants became vulnerable to deportation.

One Attorney Saved Renunciants from Loss of Citizenship

Northern California attorney Wayne M. Collins represented nearly all of the renunciants. Collins obtained a court order that stopped deportation ships from sailing. Then, over a period of decades ending in 1968, he represented the renunciants in seeking to regain their citizenship, and was successful in almost all of the cases.

"Disloyalty" Stigma Lingers

Although as a result of legislation signed by President Reagan in 1988 the government paid $20,000 in redress and the President apologized for the race-based wartime incarceration, neither Congress nor the President has withdrawn the government's mischaracterization of no-nos and renunciants as "disloyal." Sadly, the Japanese American Citizens League echoed that mischaracterization and failed to acknowledge their civil rights protest. As Daniels' book The Japanese American Cases says, many "Nikkei, as well as other Americans, have never forgiven the renunciants. Many public figures have pretended that they did not exist."